Investigación Aplicada

Influence of anchorage on flexural strength of beams strengthened with CFRP sheets

Influência da ancoragem na resistência à flexão de vigas reforçadas com mantas de PRFC

Influencia del anclaje en la resistencia a la flexión de vigas reforzadas con mantas de PRFC

Influence of anchorage on flexural strength of beams strengthened with CFRP sheets

Revista de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Control de Calidad, Patología y Recuperación de la Construcción, vol. 9, no. 1, 2019

Asociación Latinoamericana de Control de Calidad, Patología y Recuperación de la Construcción, A. C.

Received: 29 September 2017

Accepted: 18 October 2018

Published: 30 December 2018

Abstract: In order to evaluate the influence of anchorage on the flexural strength of beams strengthened with Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) sheets, the experimental results of 126 tests in the literature and of an unprecedented series with 4 reinforced concrete beams, tested by these authors, were analyzed. The parameters affecting the performance and the strength of the beams are evaluated, and the design criteria of fib Bulletin 14 (2001) and ACI 440-2R (2008) are discussed. It was observed that, even with auxiliary devices in the PRFC anchorage, premature failure is possible, and that both theoretical recommendations lead to safe estimates, but excessively conservative in cases where the anchorage of the PRFC sheet is properly done.

Keywords: reinforced concrete, flexural strengthening, CFRP sheets, anchorage.

Resumo: Buscando avaliar a influência da ancoragem na resistência à flexão de vigas reforçadas com mantas de Polímero Reforçado com Fibra de Carbono (PRFC), foram analisados os resultados experimentais de 126 ensaios presentes na literatura e de uma série inédita, ensaiada pelos autores, com 4 vigas de concreto armado. São avaliados os parâmetros que afetam o desempenho e a resistência das vigas, e discutidos os critérios de dimensionamento do fib Bulletin 14 (2001) e ACI 440-2R (2008). Observou-se que, mesmo com dispositivos auxiliares na ancoragem do PRFC, falhas prematuras são possíveis, e também que ambas as recomendações teóricas conduzem a estimativas a favor da segurança, porém excessivamente conservadoras nos casos onde a ancoragem da manta de PRFC é feita adequadamente.

Palavras-chave: concreto armado, reforço à flexão, mantas de PRFC, ancoragem.

Resumen: Buscando evaluar la influencia del anclaje en la resistencia a la flexión de vigas reforzadas con mantas de Polímero Reforzado con Fibra de Carbono (PRFC), se analizaron los resultados experimentales de 126 ensayos presentes en la literatura y de una serie inédita de los autores, con 4 vigas de hormigón armado. Se evalúan los parámetros que afectan desempeño y resistencia de vigas, y se discuten los criterios de dimensionamiento del fib Bulletin 14 (2001) y ACI 440-2R (2008). Se observó que, incluso con dispositivos auxiliares en el anclaje del PRFC, fallos prematuros son posibles, y que ambas recomendaciones conducen a estimaciones seguras, pero excesivamente conservadoras en los casos en que el anclaje de la manta de PRFC se realice adecuadamente.

Palabras clave: hormigón armado, refuerzo de la flexión, mantas de PRFC, fondeadero.

NOMENCLATURE

c – height of the block of re

a – shear span

bf – width of the layer of CFRP

bw – width of the beam

c – height of the block of rectangular compression equivalent of the concrete

c1 – factor obtained by calibration of results (equal to 0.64 for CFRP)

d – effective beam height

d’ – centroid position of the compressed reinforcement

fc – concrete compression strength

fctm – average tensile strength of concrete

ffe – effective strength of the CFRP

fs – strength in the steel of the tensile reinforcement

fs’ – steel strength of the compressed reinforcement

fys – yield strength of the tensile reinforcement

fys’ – yield strength of the compressed reinforcement

h – height of the beam

k b – geometric factor

kc – constant that considers the compacting of the concrete during the concreting

l b – anchoring length of the CFRP sheet

l – clamping width

n – number of layers of CFRP

tf – thickness of the CFRP

x – position of the neutral axis

Af – area of reinforcement applied to the beam

As – steel area of the tensile reinforcement

As’ – steel area of compressed reinforcement

CC – compression component due to the concrete portion

CS – compression component due to compressed reinforcement

Ef – modulus of elasticity of the CFRP

Es – modulus of elasticity of steel

Fcc – compression resulting

L – total beam length

M – moment applied during the experimental test

M R – resistant moment in the cross section of the beam

MRteo – resistant moment estimated by the recommendations

Mu – experimental ultimate moment

MACI – ultimate moment according to the recommendations of ACI 440-2R (2008)

M fib – ultimate moment according to the recommedations of fib Bulletin 14 (2001)

MV1 – experimental ultimate moment of the beam V1

N fa,max – maximum force that can be applied to the reinforcement of the beam

P – applied load in the experimental test

R² – coefficient of correlation of the results

Tf – tensile component due to the fiber reinforcement portion

Ts – tensile component due to the tensile reinforcement

α – reduction coefficient due to the propagation of inclined cracks

β1 – coefficient that determines the approximation of the resultant compression curve of the concrete to a rectangle according to the recommendations of ACI 440-2R (2008)

εbi – strain found in the covering of the tensile reinforcement in the beam before the strengthen

εc – concrete strain

εcu – concrete ultimate strain

εf – carbon fiber strain

εfd – limit value of fiber strain to be adopted in the sizing and verification of reinforcement

εfe – effective strain in the CFRP

εfu – ultimate strain observed in the polymer at the moment of failure

εs – strain in the tensile reinforcement

εs’ – strain in the compressed reinforcement

εys – yield strain of the flexural reinforcement

r – rate of the reinforcement of the beam before the strengthen

rr – beam reinforcement ratio after strengthen

∅ – reinforcement bar diameter

ψ – coefficient that determines the approximation of the resulting curve of concrete compression to a rectangle, according to the recommendations of fib Bulletin 14 (2001)

INTRODUCTION

Among the techniques used for the strengthening of reinforced concrete structures, we highlight the systems that use Fiber Reinforced Polymers (FRP), for presenting low weight and high tensile and corrosion strength, and the Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers (CFRP) that have shown significant acceptance for more than two decades due to their high values of strength, stiffness and durability, as well as the ease of installation when compared to other types of fibers (Monti and Liotta, 2007). In the specific case of flexural reinforcement of reinforced concrete beams, several researchers show that the use of sheets of CFRP is an effective methodology, highlighting the works of Rafi et al. (2008), Khan and Fareed (2014) and Hawileh et al. (2015).

However, it is important to feature that premature failures are associated with its use. In the case of flexural reinforced beams, this brittle fracture may occur due to the detachment of the carbon fiber from the concrete substrate, which may limit the increase in strength provided by the reinforcement. This mode of brittle ruin is usually associated with deficiency in the anchorage of the reinforcement system, which makes the use of additional devices recommended, such as band clipping of CFRP sheet (see Benjeddou et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2011, Kim and Shin, 2011, among others).

This work presents a series of experimental tests on reinforced concrete beams strengthened with CFRP sheets, carried out with the objective of evaluating the influence of the anchorage in the reinforcement structural performance. In addition, a large database was set up, with experimental results selected from the work of different authors. This database is used to discuss the influence of different parameters on the performance of reinforcement with CFRP sheets and to evaluate the performance of theoretical predictions of strength obtained using the recommendations presented by ACI 440-2R (2008) and fib Bulletin 14 (2001).

CFRP STRENGTHENED BEAMS

Failure modes

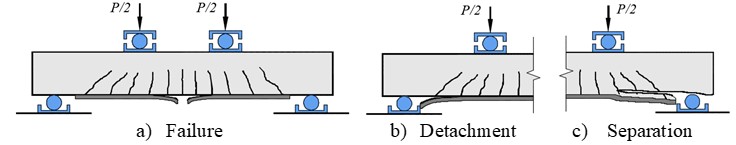

Teng et al. (2003) state that beams strengthened to flexure with CFRP sheets may exhibit brittle failure modes, for instance: by exhaustion of the strength of the CFRP (see Figure 1a); detachment of the reinforcement at the interface with the concrete (see Figure 1b); and separation of the reinforcement together with the concrete covering of the flexural reinforcement (see Figure 3c). The failure of the CFRP sheet can occur in weakly reinforced beams by flexure, being a brittle mode of failure since the CFRP presents linear-elastic behavior until the failure. The detachment of the sheet may occur due to lack of the anchorage of reinforcement, excessive cracking of the beam or, faults in its bonding process. The separation of concrete cover layer can be caused by shear strengths at the interface between concrete and CFRP due to the difference between the moduli of elasticity of these materials, which can be amplified by the corrosion of the bending reinforcement.

Flexural Strength

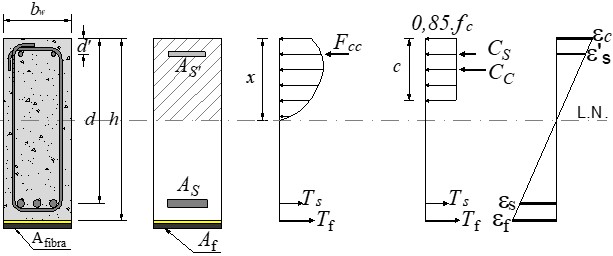

The behavior of a reinforced concrete beam strengthened with CFRP and subjected to bending can be expressed according to the diagram of Figure 2. In this analysis, it’s considered that the ratio of the reinforced beam framework is equivalent to the sum of the initial reinforcement rate with contribution from the reinforcement, as presented in (1).

Where: is the rate of the reinforcement of the beam before the strengthening; is the area of reinforcement applied to the beam; is the modulus of elasticity of the CFRP; is the modulus of elasticity of steel; is the width of the beam; is the height of the beam.

ACI 440-2R (2008)

The American code ACI 440-2R (2008) presents recommendations for the sizing of reinforcement using CFRP. To determine the flexural strength of reinforced concrete beams reinforced with carbon fiber sheets, (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9) and (10) are used.

Where: is the limit value of fiber strain to be adopted in the sizing and verification of reinforcement to avoid premature fiber failure; is the number of layers of CFRP; is the thickness of the CFRP; is the ultimate strain observed in the polymer at the moment of failure; is the effective strain in the CFRP; is the position of the neutral axis; is the strain found in the covering of the tensile reinforcement in the beam before the strengthen; is the effective strength of the CFRP; is the effective beam height; is the strain in the compressed reinforcement; is the strength in the steel of the compressed reinforcement; is the centroid position of the compressed reinforcement; is the strain in the tensile reinforcement; is the strength in the steel of the tensile reinforcement; is the steel area of the tensile reinforcement; is the steel area of compressed reinforcement; is a coefficient that determines the approximation of the resultant compression curve of the concrete to a rectangle, being 0.85 for concrete with fc values lower than 28 MPa and there being a linear decrease of 0.05 for each 7 MPa above that limit of strength, the minimum value for such a coefficient, according to ACI 318 (2014), is 0.65; is the tough moment in the cross section of the beam.

fib Bulletin 14 (2001)

The fib Bulletin 14 (2001) presents recommendations for the dimensioning of flexural reinforced beams with CFRP and adopts a calculation philosophy like that adopted by ACI 440-2R (2008). The same equations presented by the ACI are used in this document, differentiating only the following parameters: the coefficient β1 in it is called of ψ and equals to 0.8, independent of the class of strength of the concrete; and the strain limit of the fiber, which is calculated by (11), whose parameters are found by means of (12), (13), (14).

Where: is the maximum force that can be applied to the reinforcement of the beam (expressed in N); is a reduction coefficient due to the propagation of inclined cracks, adopted as 0.9; is equal to 0.64; is a constant that considers the compacting of the concrete during the concreting, being this value equal to 1 when the strengthening is applied in the underside of the beam and 0.67 in the upper face; is a geometric factor; is the average tensile strength of concrete, as expressed in Eurocode 2 (2004); is the width of the layer of CFRP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROGRAM

Characteristics of the beams

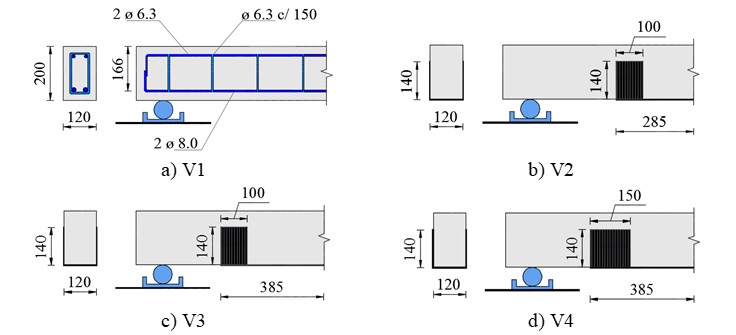

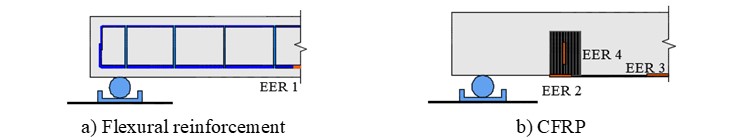

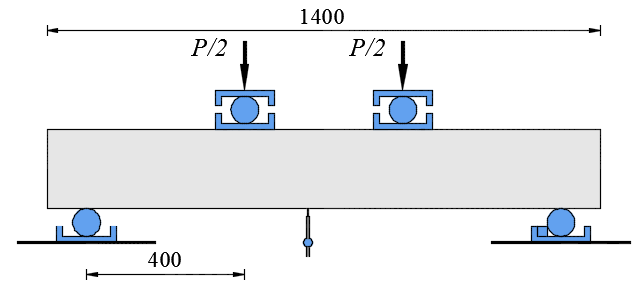

Tests were carried out on 4 reinforced concrete beams strengthened with CFRP sheets, having as variables the sheet anchorage length and width in order to evaluate their influence on both the performance and the strength of the beams. It was tested 1 reference beam without reinforcement and 3 reinforced beams with carbon fiber sheet. The rates of steel reinforcement and CFRP were kept constant. Table 1 and Figure 3 show the main characteristics of the beams. The strains in the flexural reinforcement, the reinforcement sheet and the clamping were monitored with electrical extensometers, as shown in Figure 4. Figure 5 shows the test system of the beams.

| Beam | l (mm) | l b (mm) | bf (mm) | Af (mm²) | tf (mm) | Ef (GPa) | εfu (%) |

| V1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V2 | 100 | 285 | 120 | 19.92 | 0.166 | 230 | 2.1 |

| V3 | 385 | ||||||

| V4 | 150 | ||||||

| bw = 120 mm; h = 200 mm; d = 166 mm; As = 101 mm²; fc = 20 MPa; a = 400 mm | |||||||

Discussion of Results

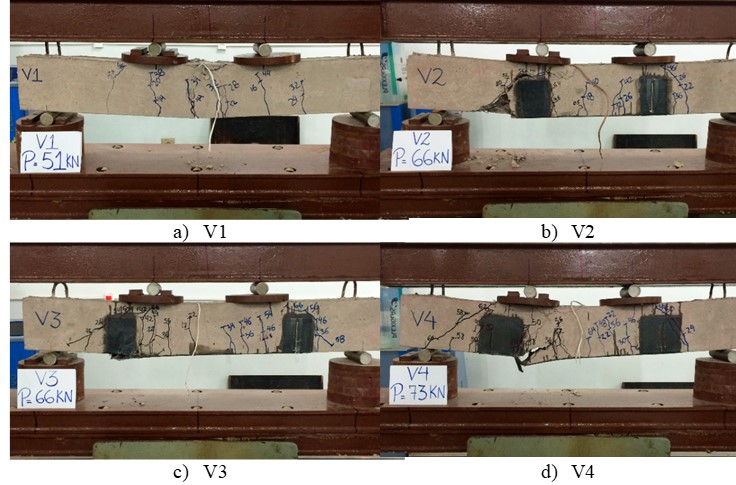

The failure mode of each of the beams tested can be visualized in Figure 6. It was observed that the reference beam failed by flexure after its longitudinal reinforcement reached high levels of strain (Figure 6a). In the V2 beam the concrete was pulled out in the zone adjacent to the clamping (Figure 6b). The V3 beam lost its strength after the fiber detachment occurred in part of the clamping contact zone (Figure 6c). However, the V4 beam failed after the detachment of the concrete covering in the region of the flexure span (Figure 6d).

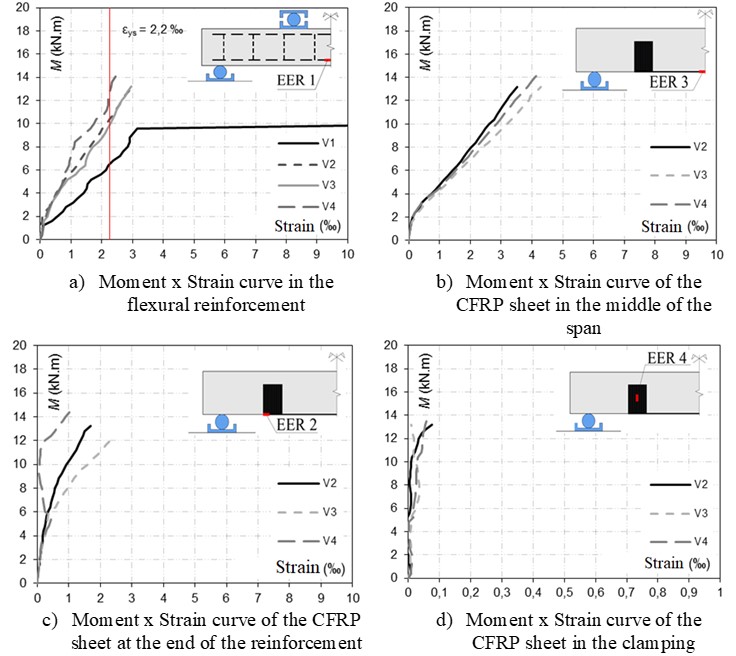

Figure 7 shows the results of strains measured in the flexural reinforcement and at different points of the PRFC. It is noticed that, in all the beams, the flexural reinforcement reached the yielding, as shown in Figure 7a. The strains in the flexural reinforcement were smaller in the beams with the sheet of CFRP for the same load levels, since the reinforcement contributed in the tensile part of the piece. In addition, it was observed that the resistant behavior of the beams with the sheet was more brittle than that of the non-reinforced beam, since after reaching the maximum strength, the readings were interrupted by the failure of the part, whereas in the beam V1, if the maximum load was reached, this loading level remained associated to a high level of strain. Figure 7b shows that both the anchoring length of the fiber and the clamping width influenced the ultimate strain of the CFRP measured in the tests, varying from 3.5 ‰ for the beam V2 to approximately 4.2 ‰ for the beams V3 and V4. In all cases, it should be noted that these values are higher than theoretically predicted by the ACI, which would be 1.9 ‰. It should be emphasized that none of the beams failed with the exhaustion of the tensile strength of the sheet of CFRP. Figure 7c shows that in all the beams the level of strain at the end of the reinforcement was smaller than that measured in the middle of the span, where the moment is maximum and that in the case of the beam V2, which failed due to the detachment of the fiber in this region, the strain limit measured was practically the same as that suggested by the manufacturer of 2.1 ‰. In Figure 7d it is possible to notice that the level of strain developed in the region of the clamping was small and that in beam V3 it clearly begins to separate before the failure.

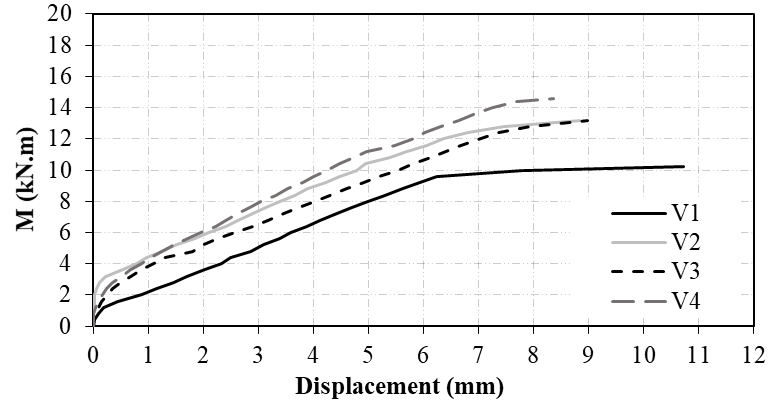

Figure 8 shows the vertical displacement curve of the beams, measured in the middle of the span. It is possible to notice that the reinforced beams presented a very similar response, showing greater rigidity than the reference beam, which failed by flexure in a ductile manner and showed large displacements when reaching the moment of yield of its flexural reinforcement. As seen, all the reinforced beams failed abruptly, with failure occurring in different regions of the CFRP.

Table 2 presents the final loads of the tested beams and compares the strength of the reinforced beams with the sheet of CFRP with the reference beam (V1), in order to determine the increment of strength generated by the reinforcement. In addition, the experimental strength of the beams is compared with theoretical estimates obtained following the recommendations of the ACI and fib14. From these results, it was observed that the increase of the anchoring length of the beam V3 in relation to the beam V2 did not result in an increase of strength, and that the increase of the clamping width was responsible for the greater strength of the beam V4 in relation to the beam V3. It was also observed that the use of ACI would result in predictions of strength against safety for beams V2 and V3, while fib14 presented results in favor of safety.

| Beam | Mu (kN.m) | Mu / M V1 | Mu / M ACI | Mu / M fib |

| V1 | 10.2 | 1.00 | - | - |

| V2 | 13.2 | 1.29 | 0.94 | 1.14 |

| V3 | 13.2 | 1.29 | 0.94 | 1.14 |

| V4 | 14.6 | 1.43 | 1.04 | 1.26 |

DATABASE

Methodology of collection and analysis of data

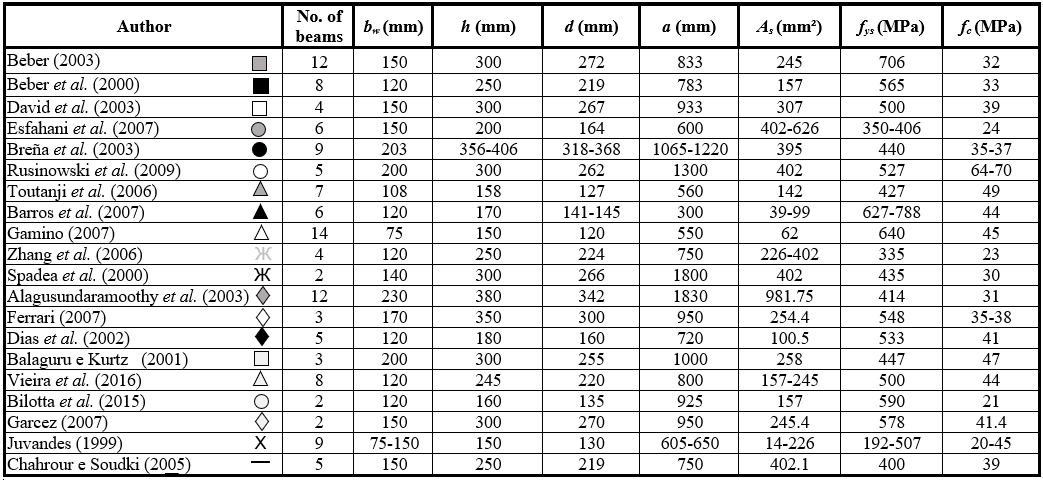

In addition to the experimental program, a database was collected with the results of 126 tests of 20 authors, involving flexural reinforced beams with the sheet of CFRP. As a criterion for the choice of beams, only those that failed by bending, without initial loading and externally bonded reinforcement, were selected. The objective of this data analysis is to evaluate the influence of the main variables on the flexural strength of reinforced beams with CFRP.

The analysis of the database involves the comparison of the experimental results with the theoretical estimates obtained using the ACI and fib 14. Thus, it was calculated the values of average, coefficient of variation and standard deviation of the ratio between the experimental ultimate moment and the theoretical resistant moment (Mu/M Rteo), and finally, the percentage of safety results (Mu/M Rteo <1) was evaluated. In order to evaluate the precision of the theoretical models, graphs are presented that compare the moment of experimental failure (M u) by the function of the predicted resistant moment (M Rteo), in order to analyze if the tendency of the obtained results approaches the ideal condition (Mu=M Rteo).

As previously noted, the performance of the reinforcement with sheet of CFRP is directly related to the quality of fiber anchoring to concrete. Therefore, the beams of the database were divided into 3 groups: group 1 for situations where the bonding of the sheet stretched from the center of the beam to the support or beyond; the group 2 with beams in which the glue of the sheet did not extend to the support; and the group 3 with beams in which external devices were used to aid in reinforcement anchorage, such as screws or restrainers. It should be noted that this type of anchorage is considered by several authors as the most favorable for anchoring the CFRP sheet, since that the device is made of this same material.

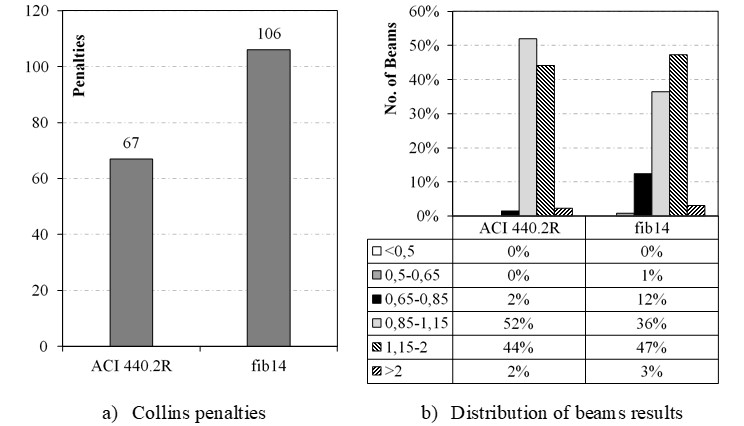

Another method used was the Collins (2001) criterion, known as Demerit Points Classification (DPC), in which the values of Mu/M Rteo were classified in ranges from "extremely dangerous" to "extremely conservative", with performance of the theoretical model defined as a number resulting from the sum of the products from Mu/M Rteo by their corresponding score, according to the classification. Table 3 presents a summary of the characteristics of the beams of the database, as well as the symbology used by the authors to identify the figures. Table 4 shows a summary of the variables related to the reinforcement with carbon fiber sheet of the beams of the database. Table 5 presents the parameters related to Collins DPC (2001).

Finally, were prepared graphs which relate the experimental strength of the beams to the predicted theoretical failure (Mu/M Rteo) according to the number of layers of CFRP sheets, as well as the reinforcement ratio after strengthening in relation to the initial reinforcement (ρr/ρ). The purpose of these charts is to analyze if the hypotheses adopted by the theoretical models present adequate correlation with the existing experimental evidence.

| Author | No. of beams | No. of layers | b f (mm) | tf (mm) | Af (mm2) | E f (GPa) | efu (‰) |

| Beber (2003) | 2 | 1-6 | 50-150 | 0.1-1.4 | 10-140 | 240 | 12-14 |

| Beber et al. (2000) | 8 | 1-10 | 120 | 0.011 | 1.3-13.2 | 230 | 15 |

| David et al. (2003) | 4 | 2-4 | 50 | 1.2 | 120-240 | 150 | 15 |

| Esfahani et al. (2007) | 6 | 1-2 | 100-150 | 0.176 | 17.6-52.8 | 237 | 12 |

| Breña et al. (2003) | 9 | 1-2 | 50-100 | 0.165-1.2 | 16.5-104 | 62-230 | 12-16 |

| Rusinowski et al. (2009) | 5 | 1-2 | 50-120 | 1.4 | 140-168 | 155-300 | 9-15 |

| Toutanji et al. (2006) | 7 | 3-6 | 102 | 0.165 | 50.5-101 | 110 | 6 |

| Barros et al. (2007) | 6 | 1-3 | 9.6-80 | 0.1-1.4 | 13.4-40.3 | 158.8-240 | 15-17 |

| Gamino (2007) | 14 | 1-2 | 75 | 0.11-0.13 | 8.2-16.5 | 230-235 | 15 |

| Zhang et al. (2006) | 4 | 1-2 | 120 | 0.11 | 13.3-26.6 | 235 | 14.27 |

| Spadea et al. (2000) | 2 | 1 | 80 | 1.2 | 96 | 152 | 15.1 |

| Alagusundaramoothy et al. (2003) | 12 | 1-3 | 76-203 | 1.4-4.7 | 36.4-975 | 48-228 | 11.5-15 |

| Ferrari (2007) | 3 | 1-3 | 16.5 | 0.17 | 2.8-8.4 | 50 | 13 |

| Dias et al. (2002) | 5 | 1-2 | 20-70 | 0.1-1.4 | 15.5-28 | 200-240 | 11-15 |

| Balaguru e Kurtz (2001) | 3 | 2-5 | 152 | 0.071 | 21.6-54 | 200 | 6 |

| Vieira et al. (2016) | 8 | 2-5 | 100 | 0.166 | 33.2-83 | 230 | 21 |

| Bilotta et al. (2015) | 2 | 1-2 | 40 | 1.4 | 56-112 | 171 | 12 |

| Garcez (2007) | 2 | 1-2 | 150 | 0.165 | 247-49 | 227 | 15 |

| Juvandes (1999) | 9 | 1 | 50 | 1.2 | 60 | 155 | 19 |

| Chahrour e Soudki (2005) | 5 | 1 | 100 | 1.2 | 120 | 155 | 19 |

| M exp/M Rteo | Classification | Penalty |

| < 0.50 | Extremely Dangerous | 10 |

| (0.50 - 0.65) | Dangerous | 5 |

| (0.65 - 0.85) | Low Safety | 2 |

| (0.85 -1.15) | Proper Safety | 0 |

| (1.15 - 2.00) | Conservative | 1 |

| ≥ 2.00 | Extremely Conservative | 2 |

Discussion of Results

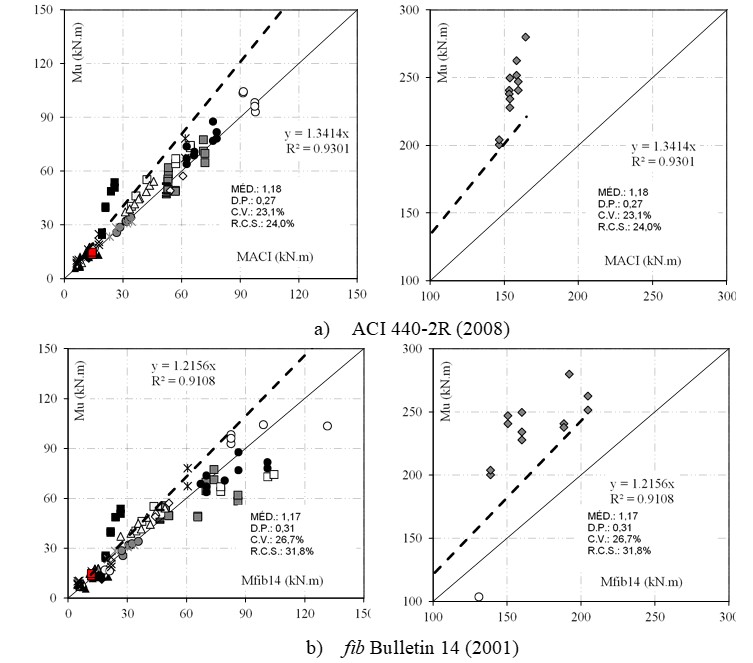

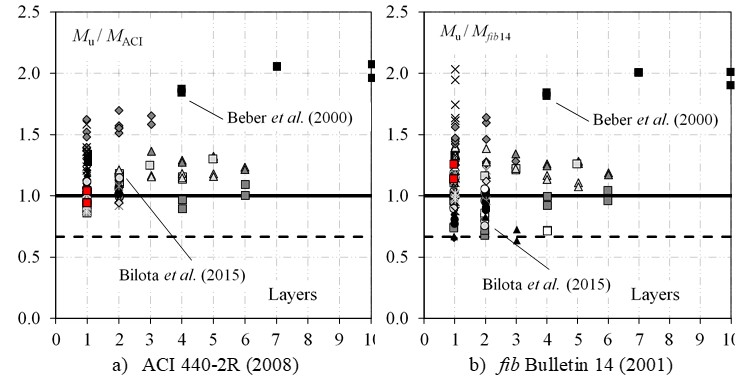

Figure 9 shows the graphs that confront the experimental strength of the database with the theoretical predictions, including in red, the experimental results tests of this research. It was observed that the two theoretical models presented similar performance in relation to the average of the results, but with fib 14 showing greater dispersion and higher percentage of results against safety. Moreover, the tested beams fit well in the trend of results observed for the larger universe generated by the database.

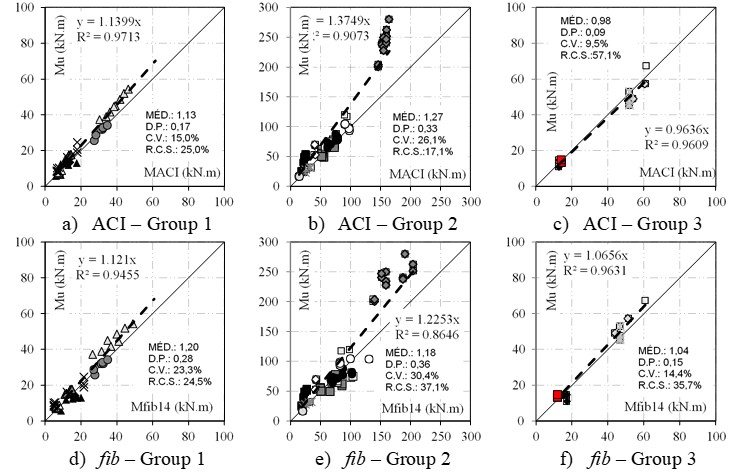

In order to evaluate the influence of the type of anchorage of the reinforcement with CFRP in the performance of the theoretical predictions, Figure 10 divides the general data presented in Figure 9, classifying them by type of anchorage in 3 distinct groups. For group 1, ACI presented an average closer to 1.0, as well as a lower dispersion of results and approximately the same number of values against safety, when compared with fib 14. In group 2, this behavior was reversed, and fib 14 showed lower average, but still with greater dispersion and greater percentage of results against the safety. For the beams of group 3 the theoretical methods presented similar performance, with the ACI showing again less dispersion.

As seen, using Collins criterion (2001), it is possible to establish scores for the two recommendations, based on the sample space of the collected database, as shown in Figure 11. It is observed that the ACI presents a lower penalty according to the criterion adopted.

Figure 12 analyzes the influence of the number of layers of CFRP on both reinforcement performance and theoretical methods. It is noticed that there is a trend of more conservative results as the amount of layers increases, which is justified by the fact that both recommendations limit the strain of CFRP. For the ACI, this trend is slightly higher, since in its equation the number of layers is used, which penalizes the strength estimation of reinforced beams with a high number of layers. In contrast, in fib 14 this factor is not considered.

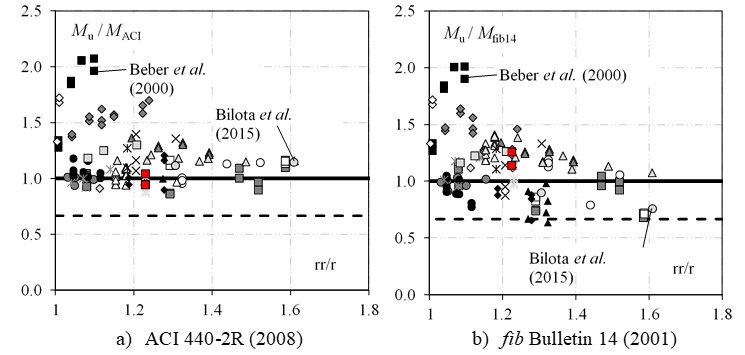

Figure 13 shows the influence of the proportion between the reinforcement ratio after the strengthening and the flexural reinforcement ratio (ρr/ρ). There is a trend of less conservative results as ρr / ρ increases, and for values above 1.4, ACI tends to stabilize this trend, avoiding estimates of strength against safety. However, the same was not observed for fib 14, whose predictions approached the dashed line, which expresses the limit of the design strength.

Figures 12 and 13 show that the number of layers of CFRP is not necessarily a parameter that should be penalized in the prediction of strength of flexural reinforced beams with sheets of CFRP as defined by the ACI. This is evident from, for example, the results of Beber et al. (2000), who tested beams with up to ten layers of CFRP sheets and obtained good performance, and those of Bilota et al. (2015), whose beams tested had only one or two layers of CFRP and showed much lower performance. By analyzing Figure 13, the beams of Beber et al. (2000) present low values of ρr/ρ while those of Bilota et al. (2015) presented extreme values within the beams of this database, evidencing that ρr/ρ is a fundamental parameter to be taken into consideration in the design.

CONCLUSION

In order to observe the influence of reinforcement anchorage with CFRP on the behavior of beams resisting to flexure, an experimental study was carried out, involving tests on 4 reinforced concrete beams, varying the anchorage criteria of the carbon fiber sheets. In addition to the experimental approach, a database with results from several authors was used to evaluate the influence of different parameters on the strength of reinforced beams to flexion with CFRP sheets. These data were also used to discuss the performance of the theoretical methods proposed by fib Bulletin 14 (2001) and ACI 440-2R (2008).

As for beam tests, it was observed that the clamping width had a greater influence on the flexural strength of the reinforced beams with CFRP sheet, since the V4 beam presented the greatest strength in relation to the others, even though the anchoring length was identical to the one of the beam V3. The beams V2 and V3 presented the same values of strength, although the beam V3 presented a greater length of anchorage between them. Another important point is that, even with the strength additions of the reinforced beams in relation to the reference, the beams with CFRP sheet have failed prematurely. Finally, it was observed that the limit values of strain of the CFRP sheet assumed by the manufacturer are very conservative in face of the experimental results recorded in this research.

As for the evaluation of the theoretical models, it is verified that both the fib 14 and the ACI presented conservative results in relation to the Mu/M Rteo ratio, which in practice should guarantee predictions of strength in favor of safety in most cases. It was also observed that the procedure of reducing reinforcement efficiency by means of limitations on CFRP strains, although generally in favor of safety, may become excessively conservative in cases of reinforcement where CFRP anchorage is performed properly. Finally, it is emphasized that among the evaluated parameters that affect the flexural strength of beams with CFRP sheets, it is worth noting that the ratio ρr/ρ was more relevant than the number of layers of CFRP sheets, considering the data of this database.

Acknowledgements

For the support on this and other researches, the authors thank: the Federal University of Pará (UFPA); to the Nucleus of Amazonian Development in Engineering (NDAE); to the Nucleus of Applied Structural Modeling (NUMEA); to the University Campus of Tucuruí (CAMTUC); to Eletrobras Eletronorte; to VIAPOL Ltda for donating the reinforcement material used in the experiments; and the development agencies CNPq, CAPES and FAPESPA.

REFERENCES

Alagusundaramoothy, I., Harik, I. E., Choo, C. C. (2003), Flexural Behavior of R/C Beams Strengthened with Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer Sheets or Fabric. ASCE - Journal of Composites for Constructions. 7 (4):292-301. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2003)7:4(292)

American Concrete Institute. (2014), ACI Committee 318-M. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. Farmington Hills, Michigan.

American Concrete Institute. (2008), ACI Committee 440-2R. Guide for the design and construction of externally bonded FRP systems for strengthening concrete structures. Farmington Hills, Michigan.

Balaguru, P., Kurtz, S. (2001), Comparison of inorganic and organic matrices for strengthening of RC beams with carbon sheets. Journal of Structural Engineering, 127:35-42.

Barros, J. A. O., Dias, S. J. E., Lima, J. L. T. (2007), Efficacy of CFRP-based techniques for the flexural and shear strengthening of concrete beams. Cementand Concrete Composites. Volume 29, Issue 3, Pages 203-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.09.001

Beber, A. J. (2003), “Comportamento Estrutural de Vigas de Concreto Armado Reforçadas com Compósitos de Fibra de Carbono”. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, p. 289.

Beber, J. A., Campos Filho, A., Campagnolo, J. L. (2000), “Estudo Teórico-Experimental de Vigas de Concreto Reforçadas com Tecidos de Fibra de Carbono”. IV Simpósio EPUSP sobre estruturas de concreto, São Paulo.

Benjeddou, O., Ouezdou, M. B., Bedday, A. (2007), Damaged RC beams repaired by bonding of CFRP laminates. Construction and Building Materials. Volume 21, Issue 6, Pages 1301-1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.01.008

Bilotta, A., Ceroni, F., Nigro, E., Pecce, M. (2015), Efficiency of CFRP NSM strips and EBR plates for flexural strengthening of RC beams and loading pattern influence. Composite Structures, 124:163-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.12.046

Breña, S. F., Bramblett, R. M., Wood, S. L., Kreger, M. E. (2003), Increasing Flexural Capacity of Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. ACI Structural Journal. 100:36-46.

Chahrour, A., Soudki, K. (2005), Flexural Response of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with End-Anchored Partially Bonded Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Strips. ASCE Journal of Composites for Construction. 9 (2):170-177. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2005)9:2(170)

Collins, M. P. (2001), “Evaluation of shear design procedures for concrete structures”. A Report prepared for the CSA technical committee on reinforced concrete design.

David, E., Ragneau, E., Buyle-Bodin, F. (2003), Experimental analysis of flexural behavior of externally bonded CFRP reinforced concrete structures. RILEM Materials and Structures. 38:238-241.

Dias, S. J. E., Juvandes, L. F. P., Figueiras, J. A. (2002), Comportamento de Vigas de Betão Armado Reforçadas à Flexão com Sistemas Compósitos de CFRP. Unidireccionais. Engenharia Civil UM. 14:15-28.

Dong, J. F., Wang, Q. Y., Qiu, C. C., He, D. (2011), Experimental study on RC beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. Advanced Materials Research. 213:548-52.

Dong, J. F., Wang, Q. Y., Zhu, Y. M., Qiu, C. C. (2010), Experimental study on RC beams strengthened with externally bonded FRP sheets. Journal of Sichuan University (Engineering Science Edition). 42:197-203.

Esfahani, M. R., Kianoush, M. R., Tajari, A. R. (2007), Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by CFRP sheets. Engineering Structures. 29:2428-2444. 10.1016/j.engstruct.2006.12.008

Eurocode 2 (2004), Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. Brussels, Belgium.

Ferrari, V. J. (2007), “Reforço à Flexão de Vigas de Concreto Armado com Manta de Polímero Reforçado com Fibras de Carbono (PRFC) Aderido a Substrato de Transição Constituído por Compósito Cimentício de Alto Desempenho”. Tese de Doutorado, Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos da Universidade de São Paulo, p. 310.

fib Bulletin 14 (2001), Externally Bonded FRP Reinforcement for RC Structures. FIB, Lausanne.

Gamino, A. L. (2007), “Modelagem física e computacional de estruturas de concreto reforçadas com CFPR”. Tese de doutorado, Escola politécnica da universidade de São Paulo, p. 259.

Garcez, M. R. (2007), “Alternativas para Melhoria no Desempenho de Estruturas de Concreto Armado Reforçadas pela Colagem de Polímeros Reforçados com Fibras”. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, p. 241.

Hawileh, R. A., Nawaz, W., Abdalla, J. A., Saqan, E. I. (2015), Effect of flexural CFRP sheets on shear strength of reinforced concrete beams. Composite Structures. 122:468-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.12.010

Juvandes, L. F. P. (1999), “Reforço e reabilitação de estruturas de betão usando materiais compósitos de “CFRP”. Tese de Doutorado, Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto, p. 302.

Khan, A. R., Fareed, S. (2014), Behaviour of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by CFRP wraps with and without end anchorages. Procedia Engineering. 77:123-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.07.011

Kim, H. S., Shin, Y. S. (2011), Flexural behaviour of reinforced concrete (RC) beams retrofitted with hybrid fiber reinforced polymers (FRPs) under sustaining loads. Composite Structures. 93:802-11.

Monti, G., Liotta, M. A. (2007). Tests and design equations for FRP-Strengthning in shear. Construction and Building Materials. 21:799-809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.06.023

Rafi, M. M., Nadjai, A., Ali, F., Talamona, D. (2008), Aspects of behavior of CFRP reinforced concrete beams in bending. Construction and Building Materials. 22:277-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.08.014

Rusinowsky, P., Taljsten, B., Sand, B. (2009), “Peeling Failure at the Cut-off End of CFRP Strengthened RC Beams”. Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium of the Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Reinforced Concrete Structures, Sydney.

Spadea, G., Bencardino, F., Swamy, R. N. (2000), Optimizing the performance characteristics of beams strengthened with bonded CFRP laminates. Materials and Structures. 33:119-126.

Teng, J. G., Smith, S. T., Yao, J., Chen, J. F. (2003), Intermediate crack-induced debonding in RC beams and slabs. Construction and Building Materials. 17:447-462. 10.1016/S0950-0618(03)00043-6

Toutanji, H., Zhao, L., Zhang, Y. (2006), Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with CFRP sheets bonded with an inorganic matrix. Engineering Structures, 28:557-566. 10.1016/j.engstruct.2005.09.011

Vieira, M. M., Santos, A. R. S., Mont’Alverne, A. M., Bezerra, L. M., Montenegro, L. C. S. and Cabral, A. E. B. (2016), Experimental analysis of reinforced concrete beams strengthened in bending with carbon fiber reinforced polymer. IBRACON Structures and Materials Journal. 9 (1) pp. 123:152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-41952016000100008

Zhang, A., Jin, W., Li, G. (2006), Behavior of preloaded RC beams strengthened with CFRP laminates. Journal of Zhejiang University SCIENCE A. 7:436-444. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.2006.A0436

Author notes

mpinaf@gmail.com

Additional information

Cite as: M. P. Ferreira, M. H. Oliveira, A.

F. Lima Neto, L. S. Tapajós,

A. Nascimento, M. C. Freire (2018), "Influence

of anchorage on flexural strength of beams strengthened with CFRP sheets",

Revista ALCONPAT, 9 (1), pp. 30 – 47, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21041/ra.v9i1.269

Legal Information: Revista ALCONPAT is a quarterly publication by the Asociación Latinoamericana de Control de Calidad,

Patología y Recuperación de la Construcción, Internacional, A.C., Km. 6 antigua

carretera a Progreso, Mérida, Yucatán, 97310, Tel.5219997385893, alconpat.int@gmail.com,

Website: www.alconpat.org

Responsible editor: Pedro

Castro Borges, Ph.D. Reservation of rights for exclusive use

No.04-2013-011717330300-203, and ISSN 2007-6835, both granted by the Instituto

Nacional de Derecho de Autor. Responsible for the last update of this issue,

Informatics Unit ALCONPAT, Elizabeth Sabido Maldonado, Km. 6, antigua carretera a Progreso, Mérida, Yucatán, C.P. 97310.

The views of the authors do

not necessarily reflect the position of the editor.

The total or partial

reproduction of the contents and images of the publication is strictly

prohibited without the previous authorization of ALCONPAT Internacional

A.C.

Any dispute, including the

replies of the authors, will be published in the third issue of 2019 provided

that the information is received before the closing of the second issue of 2019.